Have you ever had a hard time finding your language in a web interface? The Universal language picker aims to solve this problem by accepting any valid input from the user and associating it with the language value stored in the software.

The interface of MediaWiki is available in literally hundreds of languages, where many other major websites only care about English, and maybe a handful of other “major” languages.

The problem is that, with the number of available languages growing, it has become difficult to find the one you’re looking for. Especially if you don’t know in what language it’s displayed, or how the languages are ordered.

Context

The main focus of the Multimedia usability project right now is on developing a new upload wizard, to replace the insanely complicated current upload form on Wikimedia Commons. It’s not going as fast as I expected, but we’ve made some great progress recently.

A few months ago, we did some “hallway testing”: we asked some of our co-workers (who aren’t necessarily wiki-experts) to try out the upload wizard. As they were using it, we watched them and tried to identify what was confusing, in order to improve the interface & interaction with the user.

It was really interesting, as they were all using the upload wizard differently. One was an “explorer,” who would expand each and every sub-menu in order to better understand the options offered to her. Another would just try to proceed as fast as possible, get the job done and get it over with. It was a sort of rehearsal for our then-upcoming User experience (UX) study, and we learned a lot.

Where’s my Hindi?

During the testing, one of our victims was Aradhana Datta Ravindra, the Project Manager for the Bookshelf project. Aradhana was born and raised in India, and Hindi is her mother tongue.

Our prototype makes it possible to add descriptions in multiple languages. After uploading her picture, Aradhana added a description in English, then naturally tried to add one in Hindi. The problem is, she couldn’t find Hindi in the list.

The interface we use to select the language of each description is a basic drop-down menu, similar to the one already available on the current upload form.

On Commons, the list is ordered by ISO 639-1 code (sort of) but displays the name of the language in this language. For instance, Chinese is displayed as 中文 but listed at the end of the list, because its language code is ‘zh’. You have no way of knowing how languages are sorted.

In our case, the list was ordered slightly differently. It would show the same thing, but ordered as the characters appear in the UTF-8 tables. However, the problem was similar in both cases: the user couldn’t know how to find their language in the list.

We’re not talking about a 10-item-long list. We’re talking hundreds of languages (356 at the time of writing). So, if you don’t know where to look, it can take a while to browse the whole list.

When Aradhana started to look for Hindi, she realized the list was very long. She tried to type ‘h’ to jump to “Hindi” directly. Except Hindi wasn’t there. It was at the bottom of the list, with other non-latin scripts.

Later, we had a very interesting discussion about how we should show languages in the drop-down language selector.

Language displayed in the same language

One viewpoint is that, if you’re looking for a language in the list, you should know the name of this language in this language. For example, if you’re English, but you’re looking for German, you should know that the German name for “German” is “Deutsch.”

This is currently how MediaWiki handles language selection in most cases, because this system is considered to be the most language-neutral (see my previous article on this topic). The language picker in your Wikipedia (or other MediaWik-based wiki) user preferences is an example of this.

Also, although languages are usually displayed in their own language, they’re sorted by ISO code (as in the example above). On the one hand, it makes it easier to jump to your language (if you happen to know the ISO code for it, and your keyboard can input latin characters). On the other hand, the displayed names and the sorting order are inconsistent.

Language displayed in the user’s language

Another viewpoint is that all languages should be presented in the user’s language. If we consider the same example (you’re English and looking for German), the software should present you with a full list of languages with their English name, and you would be able to select “German.”

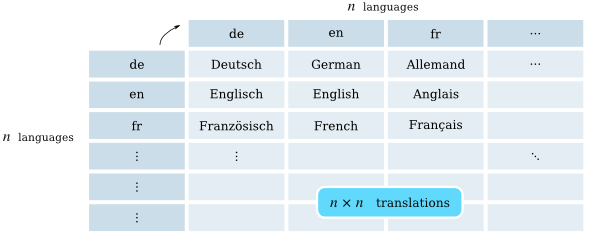

That would basically require us to know the name of all languages in all languages. For n languages, you would need a total of n × n translations. That’s a lot.

Illustration of the language table for 3 languages and its extension to an arbitrary number of languages

Even then, the table is obviously incomplete, and may stay incomplete forever. Do you know how to say “French” in Cherokee? I don’t. Wikipedia doesn’t, either (yet).

#include <mindreading>

Actually, even if we somehow managed to get a complete table, we’d still have a problem. Let’s assume for a second we’re able to know the name of every language on the planet in every other language. Some estimate the number of current languages up to ca. 7,000. That means we would have a complete table of 7,000 × 7,000 languages, i.e. ca. 49 million entries.

Now, how do we sort them?

The fact is, you can never really know what the user is going to type in. How do you know if they’re entering the ISO code, the name in English, the name in German, etc.? What if the user happens to know and regularly use the ISO 639 code, but doesn’t know the name of the language? [1] For extremely long lists, we can’t expect the user to go through the whole list if they don’t even know how it’s ordered.

It all boils down to the implementation model vs. the user model. But in this case, there are multiple users models.

Comes the Universal language picker

The main problem with the previously presented approaches is that they all assume a bijection between the displayed name and the value in the software, i.e. a one-to-one correspondence. Whether it’s displayed with the ISO code, the name in English, or whatever, there’s always only one representation possible for each language.

In the end, what we need is a way to assign multiple representations to a single language value in the software. We need a surjection that recognizes every possible input from the user and associates it with the language value stored in the software.

Surjection between all the possible inputs from the user, and the language value stored in the software

Now, what kind of interface can we use to implement this model?

A simple input field with autocomplete.

Simple as that. Forget endless drop-down menus with weird sorting orders. All we need is a simple input field with autocomplete containing all existing items in the n × n languages table. It doesn’t matter if it’s incomplete: as we get more translations, we’ll add them to the table.

Of course, we’ll need to use an arbitrary sorting order for autocomplete suggestions anyway. But by using an input field with autocomplete instead of a drop-down, the user can refine their search and dramatically decrease the size of the subset of items they’re searching in.

Ideally, the user wouldn’t even have to search: in many cases, it’s possible to guess a sensible default language, based for example on the browser language. We could pre-populate the input field with a grayed out default text that disappears if the user clicks to edit the field.

Further implications

This design has broader applications: the upload wizard is not the only place where the user might want to select a language. User preferences are an obvious example.

Given the multilingual nature of Commons, it would even make sense to add a language selector for the interface on the sign-up page. Right now, the user has to go change the language in their preferences after they’ve signed up.

I’d be delighted to hear opinions and comments about this proposed design. Do you think it would work? How technically feasible would it be?