It is the year 2031.

_(14787774963).jpg)

The Ladies’ home journal (1889) // Public domain.

As part of my work on revenue strategy for Wikimedia, I imagined three scenarios about the world in 2031 and the organization’s place in it. I used these stories to spark discussions and shift conversations from day-to-day concerns and busywork to longer-term strategic thinking.

2031: The War of the Words

.jpg)

Frederick Burr Opper on Wikimedia Commons.

Misinformation, disinformation, testudo formation.

It is the year 2031, and Wikipedia is celebrating its 30th birthday. In a world of unrest and division, Wikipedia seems strangely united. Environmental disasters due to global warming, compounded by socioeconomic crises and identity politics, have birthed a world where distrust and fear of the other are the new normal. Bad actors have never been more active online, whether they are state-funded or attempting to destabilize nations. The violence in the streets is fueled by institutional censorship, organized disinformation, and trolling campaigns that make the online atmosphere even more polluted and toxic than the actual atmosphere.

Wikipedia has fared relatively well and looks, from afar, like a surprisingly quiet haven, whose content is stable and safe from harm. In trolls, censors, and purveyors of lies, Wikipedians have found a common enemy to unite them; in tech giants, they have found unexpected allies. Big Tech companies have invested heavily in technologies to combat bad actors: they have developed tools to circumvent censorship, to make sure that they still have access to their markets. They have devised ways to identify and derank information that is not from established reputable sources, to protect the content on which their business model relies from being poisoned. They have created shared reputation scores for internet users based on all the data they collect (which are now being tested by insurance companies as well), to determine who is trustworthy online.

Faced with a deluge of disinformation and editors acting in bad faith, most Wikipedia communities have erected social and technical dams. Entire countries are blocked from editing due to sustained cyberattacks. Administrators have access to checkuser information on all accounts except each other’s. Pages on all Wikipedias are now Trust-Protected: only Trusted editors can directly edit pages and approve edits from Untrusted users. Untrusted edits are held in a review queue for seven days before being automatically discarded, which happens to 92% of them; the review backlog had been growing exponentially before the automated flush was implemented. All the product improvements developed in the past twenty years to make it easier for newcomers to contribute have been counter-balanced by more stringent policies and heavy moderation tools developed in the last ten.

This War On Lies has not been without casualties. The knowledge and communities that had been systematically left out are excluded more than ever. Historical structures of power and privilege have been reinforced by algorithms and defensiveness. More people care about guarding the temple of knowledge than about asking whose knowledge it is. The discussion on expanding the definition of reliable sources was originally intended to find ways to bring more content to Wikipedia on topics not traditionally referenced in Western academic publications. The debate ended before it even started: in a world of fake newspapers and fabricated audiobooks, oral citations are a non-starter.

The reputation system built by tech companies suffers from systemic bias, notably because it was developed quickly based on the data available to them at the time. A recent effort to measure and address the reputation gap for Internet users from Africa unexpectedly resulted in an increase of the reputation scores of most of Europe’s population, which had apparently been consistently lower than those of North American citizens. Executives have promised to take another look at the reputation scores for African users in the future.

Wikipedia’s financial sustainability isn’t a huge concern at the moment. Although readership has declined dramatically, and content is now accessed more atomically through a multitude of unbranded interfaces, tech giants have stepped in to partly make up for the decrease in donations from readers. They can’t win this fight without Wikipedia’s armies of humans, who have proved to be critical in the arms race between bad actors and tech corporations. Most affiliates have disappeared, some due to lack of funding, and most due to changes in local legal landscapes that made any relation to Wikipedia dangerous for the individuals involved.

It is unclear how, when, or if the fight will end, but it has taken an undeniable toll on the health of communities: while they were originally energized by the righteousness of their mission to defend Wikipedia against the hordes, more and more of them are retiring from the wikis due to burnout, doxxing, or simply lack of enjoyment in contributing any more.

2031: Success into oblivion

More money than we had hoped, and the cost of success.

It is the year 2031, and Wikipedia is celebrating its 30th birthday. Hundreds of parties are happening around the world and on all continents. The Wikipedia Consortium can be proud of its achievements. We did it; we achieved the ambitious goals dreamed in the 2030 strategic direction. Looking back, our success can be attributed to a series of good decisions and external events that played in our favor, for better or for worse.

A series of earthquakes, tsunamis, and violent storms in Asia, combined with civil unrest due to economic downturn, created an extended shortage of computer chips, and a prolonged increase in the price of all technological hardware that weakened tech giants worldwide. Regulators seized this opportunity to strengthen antitrust laws and break down most of the largest tech corporations, in an effort to reassert state control and power that had been eroded in the previous two decades.

The weakening of the tech giants appeared as a blessing for the civil sector, and in particular the Wikimedia movement. Public distrust of large profit-driven corporations strengthened charities and other institutional actors that were appealing to civic-minded populations. Fundraising from small-dollar donors soared and unlocked major infrastructural investments to make Wikimedia content more accessible and embeddable into all the major devices and experiences that have emerged in the past ten years. As knowledge became more structured, bite-sized, and media-driven, the concept of the encyclopedia quickly disappeared. All Wikimedia projects were folded into the Wikipedia brand in 2024, and only the grumpiest old-timers insist on still calling it Wikimedia.

This opulence also empowered Wikimedia organizations to dramatically expand globally and set up a local presence in every region, except for Asia. The movement diversified into an array of foundations, chapters, for-profit subsidiaries, affiliates, and partners, all forming the Consortium. The fundraising manna and strategic alignment happened to combine with a societal desire for social justice and equity, fueled by the rising social, political, and economic power of Millennials and Gen-Zers. This convergence started a Golden Age of Equitable Collaboration, and a multitude of successful programs to include knowledge and communities that had been historically left out by structures of power and privilege.

Yet, some members of the Consortium are raising concerns about the future. Wikipedia has become the essential infrastructure of the ecosystem of free knowledge, and anyone who shares our vision would be able to join us—if only they knew that we exist.

As the margins of big tech corporations waned, so did their scruples and seemingly benevolent intentions. Their smaller size made them both more desperate and less subject to scrutiny: when faced with a choice between not being evil and not being at all, survival comes first. Content from Wikipedia is regularly remixed and presented through better experiences than what Wikipedia can offer, provided by companies free of ideological constraints of universality and privacy. Tech corporations are aggressively exploiting the digital commons without any desire to invest in its sustainability, in hopes of regaining ground in their quest for control and profit.

When we transformed into a platform that serves open knowledge to the world across interfaces and communities, we paved the way for our own disappearing act. Knowledge has been commodified and disintermediation is now total: hardly anyone visits Wikipedia sites directly any more. 94% of fact pulls are from automated programs. (Fact pulls replaced page views as the primary access metric in 2025.) With so few humans on the sites, and no way to contribute content from third parties, content growth has fallen to pre-2003 levels, which has seemingly solved most issues of community health. The glacial pace of contribution is only sustained by expensive outreach and contribution programs; incidentally, contributions from Latin America and Africa have surpassed those from Northern America and Europe, where no such programs were initially deemed necessary.

The global expansion of the Consortium has been costly and has committed most resources to illiquid assets. For-profit ventures, initially intended to serve as a mission-aligned way to generate revenue, are barely turning any profit: there is always someone else to make the same business model more profitable. Maintaining the human and technical infrastructure of the Consortium is putting a serious toll on the Money Bin accumulated through previous fundraising, and the financial reserves are running low. As the money hose dries up, long-standing squabbles of internal governance resurface, made worse by the Consortium’s sluggish bureaucracy.

As the celebrations wind down, optimism is widespread but the future is uncertain. The Consortium was a success for a while, but is it still?

2031: Human obsolescence

Pixabay on Wikimedia Commons // CC0 1.0

The robot revolution will not be advertised.

It is the year 2031, and Wikipedia is celebrating its 30th birthday. Banners and celebratory logos have been chosen through community contests, but they saw little participation. No one is really in the mood for celebrating: last month, Wikipedia was acquired by a large media group. And even though the new owners have promised editorial independence, the few remaining editors expect the giant to kill off the site in the next few years. How did we not see this coming?

The opening of the Northern Sea Route and Northwest passage in the 2020s, following the melting of the ice caps due to global warming, caused tensions between Arctic powers. With defense spending eating more and more of national budgets, governments have increasingly relied on large corporations to take on social services and infrastructure projects. Facing pressure from their constituents for more efficiency, regulators caved to the Big Tech lobby: artificial intelligence, connected devices, and smart everything appeared as modern solutions to do more with less government money and bureaucracy. The fact that the same companies were also some of the largest defense contractors, providing digital warfare and intelligence services, was not a coincidence.

Free of regulatory shackles and fueled by generous defense contracts, Big Tech made giant leaps in machine learning, instant translation, natural language processing, and general sensemaking engines. Similarly to technologies developed during the Space Race, these digital advances made their way into many everyday commercial products and further profited tech corporations.

All the while, the Wikimedia movement slowly made progress on its 2030 strategic direction, not realizing it had already slid into irrelevance: in a bloodless and silent coup, the machines had not only risen; they had already won.

While humans were slowly sifting through books to reference facts, machines were reading and making sense of millions of pages and integrating that knowledge into their databases. While humans were struggling to keep up with current events and news, machines were combing through millions of social media posts, data from devices and wearables, and assembling information that was more relevant, more local, and more timely. While humans were writing encyclopedia articles on the same topics in dozens of languages, machines were combining all of them into a structured, language-agnostic corpus that was then served to customers in their preferred tongue, through their interface of the moment, at the level of detail they needed. Any advances made by humans were quickly integrated into digital brains.

The machines and their powerful, wealthy human masters only needed to collaborate with humans until they had learned enough from them. We thought the threat was disintermediation: tech corporations appropriating knowledge from Wikimedia websites and serving it directly to their customers, cutting Wikimedia as the intermediary. Instead, the threat was that of human obsolescence: there is no need to cut the intermediary if you can assemble the knowledge yourself in the first place.

The jury is still out on systemic bias. The reliance on technology has in a way served as a Great Equalizer: knowledge is available to all, regardless of culture, region, or language. And ever since general sensemaking engines started being able to understand and organize local social data, knowledge and news from historically disenfranchised populations have entered the global knowledge corpus. However, long-standing structures of power and privilege can still be discerned by whoever cares enough to look: the machines and algorithms are still Children of Profit, and their creators have little incentive to make them auditable and accountable.

There might have been a future for Wikimedia if the movement had figured out its unique advantage over the machines and adapted in time, but by the time we realized what was happening, it was too late. Deprived of readers, and therefore of donors and contributors, the options for survival were few. Swallowing our pride, we were the ones who went to the media giant asking for help; they agreed to host us out of pity more than interest. The new owner isn’t even planning to serve ads on Wikipedia: the low number of readers (and therefore the meager revenue from ads) isn’t worth the trouble.

Beyond the scenarios

Black swan (cygnus atratus) by Rikiwiki2 on Wikimedia Commons // CC-By-SA 4.0.

If all you’ve ever known is white swans, you think black ones can’t exist.

The point of this exercise was not to choose a scenario over another: we can’t choose what the future will look like, just like we can’t change the past. Our temporal agency is limited to the decisions we make in the present, based on our understanding of the past and the future. The goal was to provoke thinking, devise strategies, and guide decisions that would help us adapt to the variety of possible futures.

The scenarios all contained both favorable and unfavorable story elements, to ensure that people engaging with them wouldn’t be tempted to pick one as the future they favored. The actual future that would come to pass was likely to be a combination of elements from all these stories. These stories were the basis of the revenue strategy I devised in 2019.

Projecting ourselves into the future (for example, with scenarios and unexpected events) is a helpful way to chart a course for the future, and become antifragile in an uncertain world.

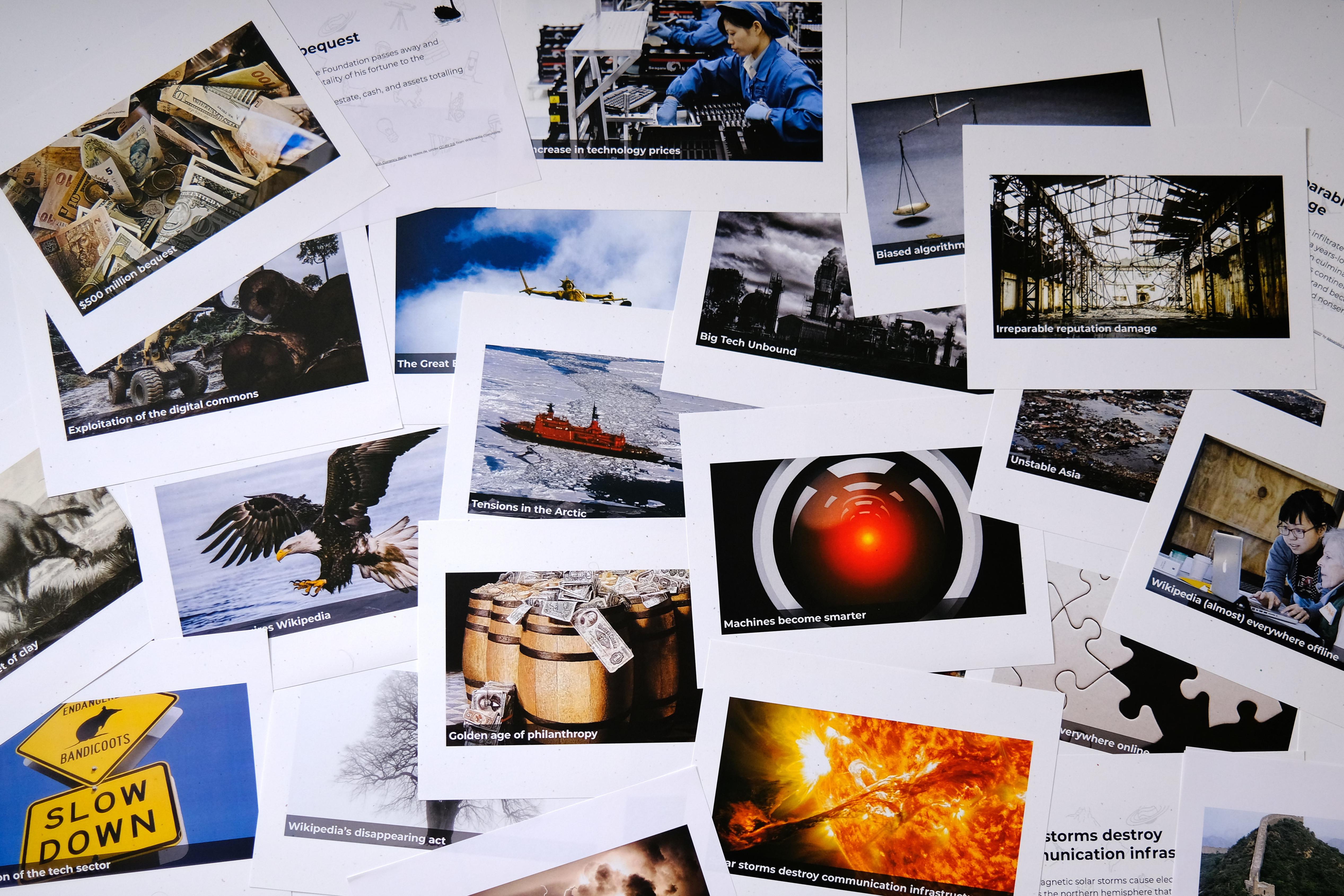

During a department retreat, I organized a workshop with Advancement staff, using full-page cards representing story elements of the scenarios, to encourage long-term thinking while tapping into the participants’ own expertise and imagination. The cards provided the framework for the discussion, but let the participants weave them together in new ways.

I also introduced “black swan” cards halfway through the activity,[1] picked at random among a few options. The goal was to prompt the participants to contend with unpredictable, wild card events and consider how their draft strategies would fare in those new circumstances.

The workshop was a high point of the retreat, and I’ve held similar workshops for Advancement and Wikimedia staff over the years. Future-oriented thinking helps build resilience by shifting the perspective of the organization’s leaders to the long view, and leading them to imagine the future consequences of current events and choices they make today.